By Julie Tomascik

Editor

Fierce, howling winds ripped through the High Plains and other areas of the state this week, leaving farm families facing devastating losses despite planning and efforts to prepare.

“A lot of the weathermen were saying last weekend that it was going to get really bad on Wednesday and could have anything from 50, 65, 80 mile per hour (mph) winds and to start preparing for that,” Jesse Wieners, a farmer in Carson County, said.

So, they did.

“We did what we could. We got all of our [irrigation] pivots faced in a certain direction, and the majority we actually had running trying to keep water on the wheat and keep the soil from blowing by trying to keep it wet,” he said. “We did everything that we could, got everything going, had everything watering.”

Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough.

The winds blew into Carson County around noon Wednesday, Dec. 15. Wieners said they had sustained winds at about 60 mph with gusts up to 70 mph.

“We weren’t as bad as what they got to the north of us, but it was enough to do damage,” he said. “And then once the wind hit, it didn’t stop until right after sunset. So, it was 60 mph wind sustained for roughly five hours. The Northern Panhandle was about 65 to 70 mph sustained with gusts to 100 for a longer period of time, probably six or seven hours.”

The devastation was evident the next morning. Wheat fields that were green are now brown, and Wieners’ crop is a total loss.

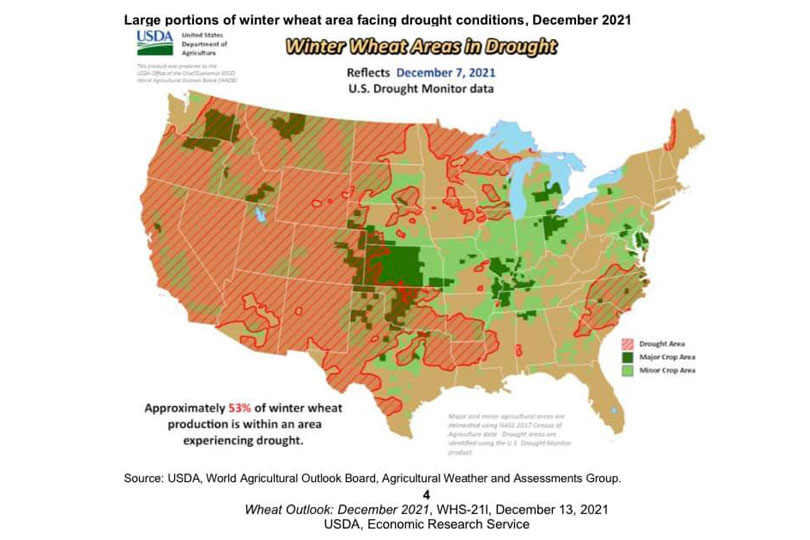

The wind storm coupled with prolonged drought left the wheat crop especially vulnerable. A Dec. 13 winter wheat report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture showed about 53% of winter wheat production is in areas experiencing drought. The Texas Panhandle is one of those areas. Wieners said the Texas Panhandle hasn’t received rain in nearly 70 days.

“All the wheat that was out there was in poor shape. It didn’t have a root system on it, or if it did, it was very shallow. So, it wasn’t established, and it couldn’t hold up to a wind like we had,” Wieners said. “The wheat that is still around is irrigated wheat that was planted really early. They had a lot of water on it, and it was established. But even around the edges of the field, the wheat blew out.”

This isn’t the first wind storm Wieners has seen, but it is the worst.

“The thing about this storm was how long it lasted,” he said. “I’ve had no-till cotton blow out before, but that was because of straight-line winds off a thunderstorm. That wind only lasted probably 30 minutes. But as far as a sustained wind this big for this long, I can’t think of an event like this, not in my lifetime.”

Despite February’s winter storm and December’s devastating winds, Wieners remains positive.

“I guess that’s why there’s only 2% of the population that do this job, because you have to love it to do it,” Wieners said. “What has me optimistic right now is we just had one of the best cotton crops I’ve ever had, and there were good prices. I’ve had more bad years than good years, but we had a good summer and a good crop this year. And I know we’re going to have more good years.”

Being a farmer takes faith, hope and love. It’s gratitude for the little moments and prayers for a brighter tomorrow.

“There’s so much out of our control. Anybody who farms knows that. You really embrace the good years, and you’re very thankful for them,” he said. “On the bad years, you thank God that you get to continue doing what you love. That’s the only way I can put it.”

I sure appreciate the commitment our farmers and ranchers put in to keep us fed and clothed. It’s a tough job but a good life, over all. I’m not a farmer but a rural Texan from a long line of farmers.

Will they come back with corn, cotton or sorghum? How will they cover the ground?

Yes Nancy everyone has a different perspective according to their location and soil types. My week is dying from drought and a lot of it will not even germinate. I will come back with a cover crop in the spring of hay grazer, Milo, are a cover crop that I can graze my cattle.