By Jennifer Whitlock

Field Editor

An anthrax case was recently confirmed in a captive white-tailed deer herd in Val Verde County by the Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC), marking the first anthrax case in Texas in 2021.

Now, TAHC is urging area ranchers and other livestock owners to be on the lookout for symptoms of anthrax and to ensure their herds are vaccinated.

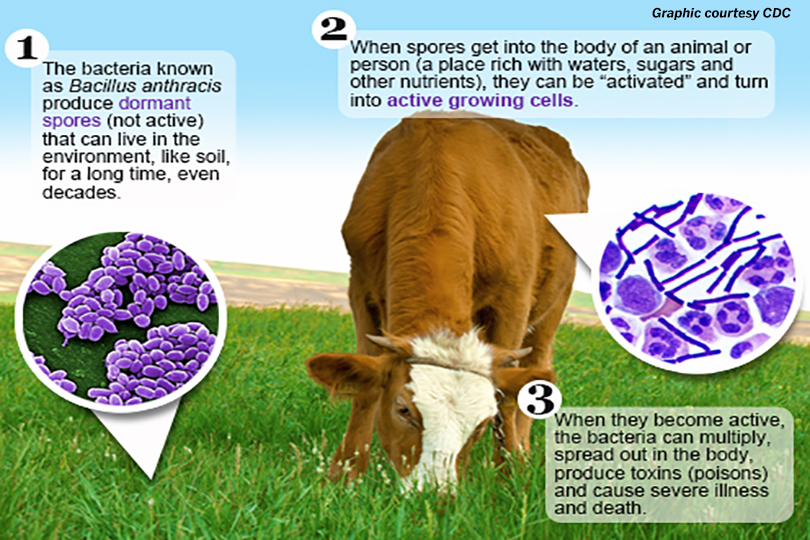

The deadly bacterial disease spreads easily through spores released into the soil from infected animals, State Veterinarian and TAHC Executive Director Dr. Andy Schwartz said.

“One of the signs of anthrax is rapid death. As soon as that animal dies, there can be some leakage of bodily fluids, blood in particular, and then that bacteria can be contracted by other animals. They essentially catch the disease from the other animal, but through contact with the carcass,” he said in an interview with the Texas Farm Bureau Radio Network. “So, it doesn’t tend to be a lot of live-animal-to-live-animal transmission. But if those animals are in the same environment and the environment is contaminated by the bacteria, then you can see many other animals in the herd affected, as well.”

Anthrax most easily infects livestock, including cattle, horses, sheep and goats, as well as wildlife like deer and antelopes. Mammals like pigs, dogs and cats may also contract the disease but appear to be more resistant than herbivores.

Spores can infect humans through abrasions in the skin. Humans may also contract anthrax by ingesting the spores in improperly cooked meat from an infected animal or through inhalation of spores.

In animals, anthrax comes on quickly and often causes death within 48 hours, Schwartz said. The incubation is variable, from as short as one day to as long as seven days after exposure before animals begin showing signs.

Generally, the symptoms are an acute fever, staggering or incoordination, and difficulty breathing followed by rapid death and bleeding from orifices. Sudden death without clinical signs is also common.

But livestock vaccinations are readily available and highly effective, according to Schwartz.

“There’s a very good vaccine available in livestock species, including cattle, horses, sheep, goats and pigs. So, we encourage producers in an area where there are known cases of anthrax in previous years or a current outbreak to vaccinate their animals,” he said. “They can do it themselves or have their veterinarian administer the vaccination, and it takes about two to four weeks for protection to develop. So, it’s good to get on top of things early.”

Immunity lasts about four months, and then the vaccination must be repeated. The vaccine also works for deer, but a veterinarian must order it for off-label use to legally vaccinate captive deer, he added.

It is rare to catch anthrax in livestock quickly enough to prevent death, but Schwartz said it does occasionally happen.

“This is a bacterial disease, and it can be treated with antibiotics if caught early enough and an animal is given other supportive care. Again, that’s a rarity to find an animal in time,” he said. “But if the outbreak is happening and if animal owners are really attentive and see an animal that’s becoming ill and can catch it early enough, they can potentially treat that animal with antibiotics.”

Although it can occur anywhere in the state, traditionally, anthrax is most often found in Crockett, Edwards, Kinney, Maverick, Sutton and Val Verde counties.

There were also cases of anthrax in cattle in the Texas Panhandle last year in Armstrong and Briscoe counties. Schwartz noted it had been several years since any cases were seen in that area, which he said underscores how durable anthrax spores can be.

“It can just lie in the soil for years or even decades, and then under the right conditions show up in susceptible species,” he said. “We do have these common areas where we see it more often. It’s been shown that these anthrax cases tend to follow the old cattle drive trails. And so the idea is that the cattle moving back in the 1800s may have spread anthrax spores into the soil, and we’re still seeing the aftereffects of that now.”

Anthrax usually pops up in periods of rain followed by hot, dry weather. Late spring and early summer are common times to see anthrax outbreaks in Texas, and they typically cease in the fall when cooler weather arrives.

The infected premises in Val Verde County are now quarantined, according to a TAHC press release. Proper disposal of affected carcasses on the premises must be completed before TAHC will release the quarantine.

The best method of disposing of an infected carcass is by burning it where it was found or as nearby as possible because burning will destroy all present bacteria.

“If a rain or something disturbed the soil and brought those spores back up, an animal may inhale them or pick them up through grazing and then perpetuate it by creating more spores,” he said. “Our preference is to try and dispose of the animal where it lies or nearby, but we realize that cannot always happen. If a carcass must be moved, try to do it in a manner where it doesn’t contaminate the surrounding environment.”

Humans are also vulnerable to the disease, so anyone coming in contact with a suspected anthrax animal death should exercise caution. Schwartz recommended people wear a long-sleeved shirt and gloves that can they dispose of afterwards and to minimize contact with any bodily fluids from the dead animal. Hands should be washed thoroughly afterward, as well.

Livestock owners with animals displaying symptoms of anthrax or that they suspect may have died from the disease should contact their veterinarian or TAHC immediately.

“The Texas Animal Health Commission regional offices are listed on our website, or you can call the main number in Austin and report suspected cases of anthrax. You can also call your veterinarian and report it,” he said. “We also partner with accredited veterinarians in the state, and they are required to report to us when they’ve made a diagnosis of anthrax. But just be sure and tell your veterinarian or the Animal Health Commission when you suspect anthrax.”

For more information about anthrax, see the TAHC anthrax factsheet.

TAHC contact information, including each regional office, is available here.

To learn about anthrax in humans, visit the Texas Department of State Health Services or the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This is great info for we small farm sheep operators in Rio Grande valley. Thank you.

So distressing! Our deer population hasn’t recovered from the last outbreak a few years ago!