By Jessica Domel

Multimedia Reporter

Long days behind the controls of a tractor or combine could become a thing of the past.

Autonomous Solutions Inc. (ASI) is one of several American companies now testing technology that could lead to driverless agricultural machinery.

“We’ve partnered with Bolthouse Farms, which is owned by Campbell Soups. On that farming operation, we’re testing the Case IH Quadtrac articulated tractors. There, we’re doing tillage and other ground preparation applications,” Kevin Cobb, business development manager for ASI’s agricultural division, said in an interview with the Texas Farm Bureau Radio Network. “We’re testing those in a leader-follower type scenario.”

In that pilot program, an autonomous tractor follows another machine driven by a human. The driver has a remote control display that allows control of the one that follows in autonomous mode.

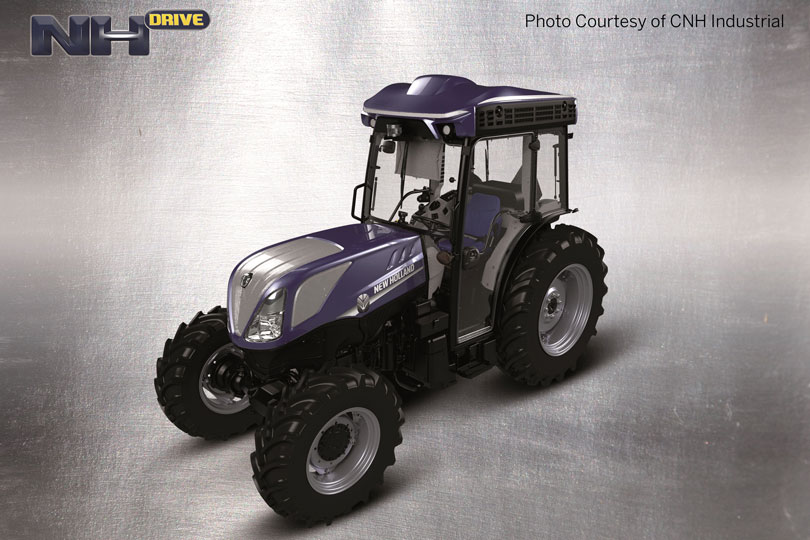

The other pilot program is at Gallo Vineyards and puts the equipment to the test in a Holland T4 orchard tractor.

“These are running simple applications like mowers,” Cobb said. “We’re looking at other things as this thing matures a little bit to be doing some spraying and other applications in the vineyards.”

The two pilot programs are set up differently. The large Case tractor works in the wide open fields of a carrot farming operation. The New Holland machine is testing in very tight quarters running down rows up to eight feet apart with trellises and grapevines.

“We expect to gain knowledge and collect lots of data,” Cobb said. “Some of this is to help evolve or continue to develop our obstacle detection. If there’s something that gets in the way of one of these machines, in order to be safe, we have to recognize it or be able to stop in time. The sensors and obstacle avoidance is a big part of what we’re going to be refining and developing.”

If two machines running ASI’s technology are in the same field and one runs into an obstacle, like a cow, the first machine can warn the second.

A notification can also be sent to the farm manager or owner so he or she can look at the cameras on the machine and decide the best way to tackle it—whether that be by honking the horn remotely, waiting for the cow to move on or shutting down the machine.

“As we’re out there in the real world, really one of the main things we’re going to learn from is what the practical challenges are that we’re going to run into because a lot of this technology can look good on paper. It can look good in the lab. We can get all excited about it, but then you go put it out in the real world and find that wow, we didn’t know that that was going to happen. Those are the kind of things we’re going to learn through these pilot programs,” Cobb said.

Over the next few years, ASI plans to work with the technology to correct any issues that may arise, while also honing in on what works best for the nation’s farmers and ranchers.

Cobb said it is likely that in the future we could see driverless tractors, combines and other equipment thanks to advances in the automotive industry and other sectors.

“We’re getting there one step at a time, but there’s still research and development going on with emerging sensor technology and the perception software,” Cobb said. “There’s also a machine learning aspect to it. These algorithms that decide which way to steer, where to go and what the best path is will all be maturing and getting better. In fact, that’s the new frontier.”

There are different levels of autonomy. One is remote supervision.

“(You) might think of it as an air traffic controller on these machines. How much the machine does on its own and how much it requires a human intervention, even though he may be remote, is a journey that we’re going to go through,” Cobb said.

The other is the leader-follower method where a driver in a leading machine directs a tractor or combine behind it.

“I would say that over the next two years, we’re probably going to continue. You’re going to see a lot of these pilot systems out t