By Jessica Domel

Multimedia Reporter

The Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) have seen an increase in the number of cattle fever ticks outside of the quarantine zone in the Rio Grande Valley.

According to TAHC, cattle fever ticks have been found on cattle outside of the established quarantine areas in Cameron, Hidalgo, Jim Wells, Jim Hogg and Willacy counties.

Many of those counties had existing quarantine areas, but TAHC reports the newly identified locations where the ticks were found were outside of the quarantine zone.

As a result, the premises where the ticks were found have been quarantined.

“Whenever we find fever ticks outside of the zone on livestock or wildlife, we quarantine those premises, and we start a systematic treatment period where we treat the animals on those premises,” Dr. Susan Rollo, state epidemiologist, said in an interview with the Texas Farm Bureau Radio Network.

TAHC also implemented movement restrictions to protect other naïve cattle.

“We also look at the properties around that place that has the fever ticks. We want to make sure there hasn’t been spread through wildlife to additional property, so those properties are quarantined and monitored for tick spread,” Rollo said.

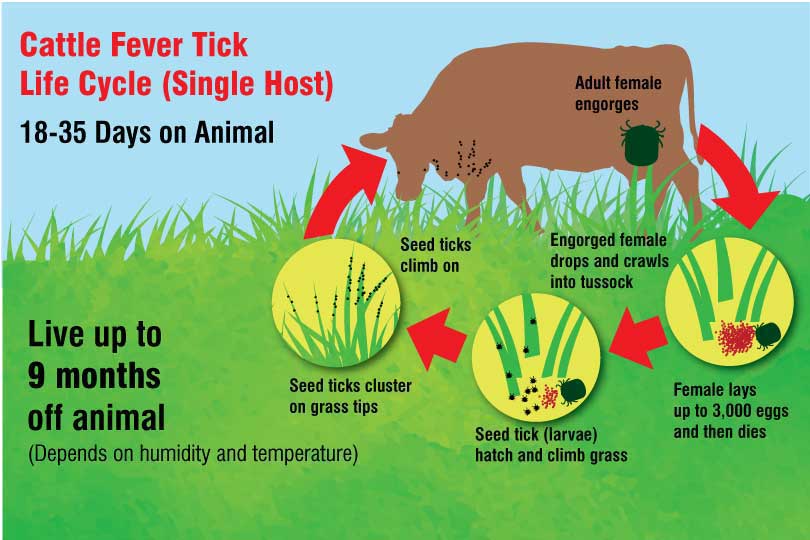

The quarantines are important, because a single cattle fever tick can lay up to 4,000 eggs.

“We can easily have a population of ticks bloom with just one cow moving to a premises with one tick on it,” Rollo said. “That’s why we trace all the animals that were sold from an infested premises to make sure we find where all those ticks could have moved and make sure we got on top of any new populations of ticks.”

The cattle fever tick and the disease it carries has the capability to cripple the Texas and U.S. cattle industries if not contained.

“The ticks can carry an organism called babesia. Cattle in Mexico have babesia, but they were introduced to this organism as calves, so they have an immunity against it,” Rollo said. “When you have a group of naïve cattle in Texas or the rest of the nation, and you introduce this organism, it can make the cattle very, very sick. It has a high death rate.”

Any time cattle are moved out of a quarantine area, they’re dipped to protect cattle in other parts of the state and nation.

“They should not stop buying cattle from South Texas quarantine areas or zones,” Rollo said. “Any animal that is moved off a quarantine area is going to be dipped, so those animals are free of ticks when they move out of a quarantine zone and go to market to be sold.”

Cattle, horses and wildlife can also carry cattle fever ticks.

“Cattle are the best host for cattle fever ticks, but we also have ticks in white-tailed deer. That’s concerning, because white-tailed deer will jump over a fence and spread ticks to other properties,” Rollo said. “We also have a huge population of white-tailed deer in South Texas now, so a lot of our issues are around the fact that we have white-tailed deer with the ticks.”

In non-hunting seasons, TAHC puts corn treated with Ivermectin in deer feeders in the quarantined zone to treat white-tailed deer, so they don’t spread the ticks from property to property.

Unfortunately, the same process does not work for nilgai antelope, which travel further than white-tailed deer traditionally do.

“Some of our new infestations we believe are due to nilgai movement out of our temporary preventative quarantine area in Cameron County,” Rollo said. “[Nilgai] are desirable to producers, because they’re good hunting animals.”

There are movement restrictions for nilgai, deer and cow hides from the quarantine areas.

“We have to scratch the hide and treat it prior to moving it off the quarantined premises,” Rollo said. “If there was a female engorged tick that was on a hide, and you carried it and threw it in your backyard, that tick could get into the ground. If you have cattle out there, that could be a risk.”

TAHC research shows feral swine are not carriers for cattle fever ticks at this time.

Cattle fever ticks are seen more often during the spring hatch in March, April and May.

The ticks do not typically feed on humans and dogs.

Cattle raisers and feeders who are concerned about ticks on their animals are encouraged to contact their private veterinarian, a TAHC regional office or USDA personnel to inspect the animal.

Additional information on cattle fever ticks is available at tahc.texas.gov.

Do you have a detailed map that shows where these ticks have found .

You can visit the Texas Animal Health Commission’s website for that information: https://www.tahc.texas.gov/animal_health/feverticks-pests/.