By Jessica Domel

Multimedia Reporter

To help prevent the spread of cattle fever ticks to unaffected areas of the state and nation, hunters who bag a white-tailed deer, nilgai, antelope, black buck or another exotic cervid in portions of the Lower Rio Grande Valley are required to have their game inspected and tested before leaving the area.

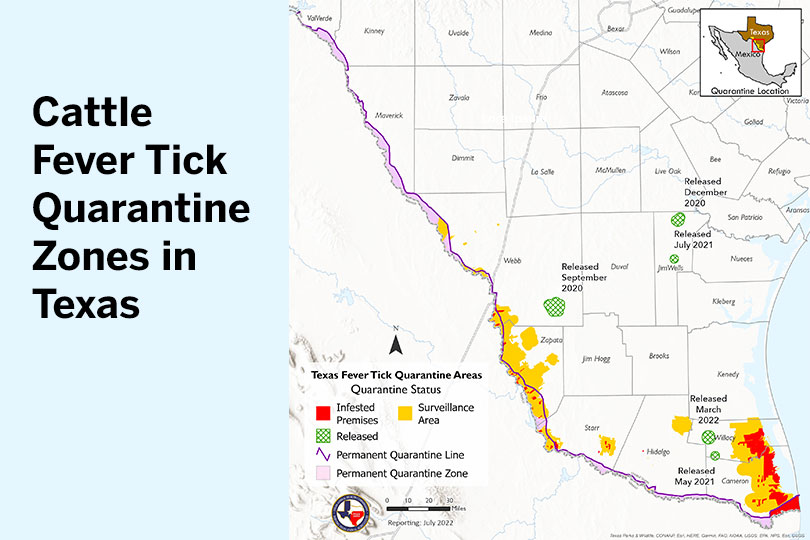

There are cattle fever tick quarantines in portions of Val Verde, Kinney, Maverick, Webb, Zapata, Starr, Hidalgo, Cameron and Willacy counties.

“The ranchers and the producers in our area are very aware of what they need to do to stop movement and stop the spread of cattle fever ticks, but a lot of hunters that come in from out of the area are not involved in this on a day-to-day basis. They really don’t know how much cattle fever ticks could impact the rest of the state that’s not in a fever tick quarantine area,” Eli Benavidez, supervising inspector for the TAHC Willacy County Fever Tick Response Office, said.

Cattle fever ticks are a significant threat to the U.S. cattle industry. They can carry the microscopic parasite, Babesia bovis, which attacks and destroys red blood cells in cattle. That can cause acute anemia and lead to high fever, enlargement of the spleen and liver, and can ultimately lead to the death of up to 90% of susceptible naïve cattle.

“If an animal leaves a quarantine area without being inspected and treated, and it’s got cattle fever ticks, that animal can be moved hundreds of miles in a matter of hours—way outside of any surveillance areas we may have,” Benavidez said in an interview with the Texas Farm Bureau Radio Network. “If that hide gets disposed of in a pasture with cattle, we may have a major outbreak based on one animal being moved outside the quarantine area.”

The inspection process takes maybe 30 minutes from the time an inspector arrives to a hunters’ location until they’re cleared.

“It’s not a very hard process,” Benavidez said. “We do encourage hunters if you know you’re in a quarantine area, and you know you want to move a hide out, a cape or whatever it may be, call early in the process. That way you’re on our radar, and we’re going in your direction while you’re skinning the animal and getting ready for the treatment.”

The animal’s hide or cape needs to be removed from the carcasses for treatment. It cannot be treated while still on the animal to ensure the meat is not contaminated.

“Have your information ready, the taxidermist you’re going to use and their address. That way, as soon as the treatment is done, we can get your permit issued and then you are free to go to your destination,” Benavidez said.

All white-tailed deer, nilgai, antelope, black buck, axis deer, kudu, aoudad sheep, red deer and other exotic cervids harvested in a cattle fever tick quarantine zone must be inspected and treated before they can be removed from the location where they were harvested.

The goal is to protect the rest of the state and the nation from cattle fever ticks.

“Imagine if a fever tick outbreak establishes outside of our quarantine area. A fever tick quarantine, at the minimum, can last at least 18 months, and I’ve seen them go longer than that,” Benavidez said. “The quarantine that I’m involved in here in Willacy County is going on nine years. Imagine the burden that puts on the producers for one, having to gather cattle.”

Based on the inspection cycle, ranchers in the impacted area may have to gather cattle every 14 days, 28 days or 90 days depending on where they are in the quarantine process.

“That is a heavy burden to put on producers to keep having to gather their cattle because then you have to hire people and fix infrastructure, working pens and all that,” Benavidez said. “It affects our marketability. People aren’t allowed to move (cattle) as freely as they used to be before they were under quarantine. That can affect a wide range of people from the small producer that has 10 head to huge ranches that run thousands of head of cattle.”

It’s also expensive for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which has to hire personnel, install dipping vats and inspection stations.

“A lot of this can be prevented if we do what we’re supposed to as far as getting animals inspected how they’re supposed to and treated before they leave,” Benavidez said.

A map of cattle fever tick quarantine zones, and the numbers to call for inspections in each county in the zones, are available at https://tahc.texas.gov.