By Jessica Domel

Multimedia Reporter

Texans who plan to travel out-of-state with their horses are encouraged to first check with the Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) and the state they’re traveling to before loading up the trailer.

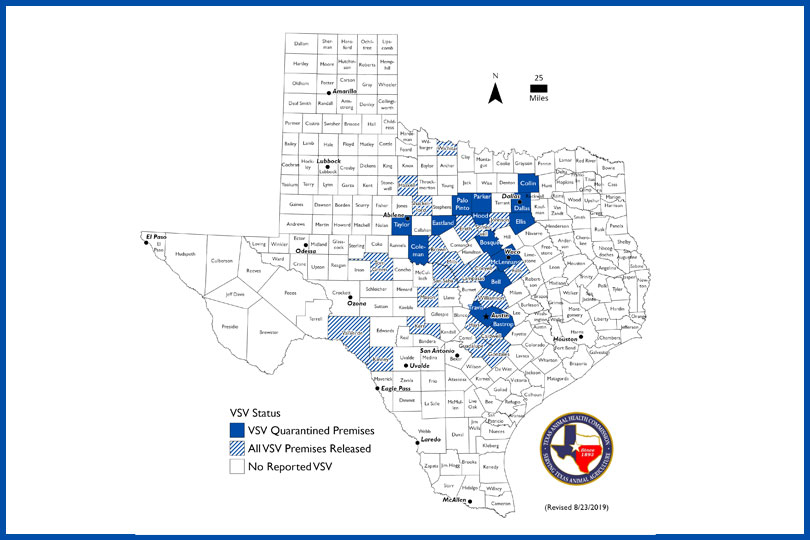

To date, 168 cases of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) has been confirmed in 36 Texas counties.

The virus, which primarily affects horses and cattle, can affect trade with other nations, so there are movement restrictions within the United States and internationally.

“If anyone is planning on taking their horse out-of-state and going into another state, we recommend that they contact that state to make sure that they’re allowed to enter,” Dr. Susan Rollo, state epidemiologist, said in an interview with the Texas Farm Bureau Radio Network. “Some of the other states have restrictions, and they’ll base it on the county.”

Each Friday, TAHC issues a news release with an updated list of counties that have quarantines and which counties have been released from quarantine.

“That’s hopefully helping the people that are trying to move their horses out-of-the-state,” Rollo said.

To date, all but one of the confirmed VSV cases in Texas have been in horses. The single bovine case was in Gonzales County.

Although there were some confirmed cases of VSV in 2015, the last outbreak was in 2014.

The state typically sees outbreaks every five to 10 years.

“We’ve had a large number of anthrax cases this year, too. In both cases, we believe that it’s due to the warmer weather following a wet spring,” Rollo said.

VSV causes blisters in horses and cattle that look similar to foot-and-mouth disease.

“If it did get into cattle, which we did have one case so far, then we have to be really cautious about getting proper samples to confirm whether if it is VSV and not something foreign like foot-and-mouth disease,” Rollo said. “We did see it in more cattle in 2014, so occasionally we do see it in cattle. It’s just not as common as in horses.”

The viral disease is spread by horses and midges.

“Even with the best defensive measures, VSV could infect a herd,” Rollo said. “Tips that could help protect livestock include: controlling biting flies, keeping equine animals stalled or under a roof at night to reduce exposure to flies, keeping the stalls clean, which would reduce the population of flies, feeding and watering stock from their individual buckets so you’re not having contaminant infection between horses or other animals and disinfecting borrowed equipment or tools prior to using them.”

Symptoms include blisters that swell and burst, leaving painful sores around the horse or cow’s muzzle, gums, teats and hooves.

“Basically the outer skin layer sloughs off, and that’s especially painful for the skin on the tongue,” Rollo explained. “The animals will have a hard time eating and drinking. It will be painful with the lesions.”

There’s no vaccine available for VSV.

“If livestock owners suspect their animals have VSV, they should contact their private veterinarian immediately,” Rollo said. “Their veterinarians will collect blood samples from the blisters or sores of the affected animal.”

If the tests come back positive for VSV, TAHC will notify the owner and quarantine their facility until the lesions heal.

“We work with the private veterinarians to make sure they submit the proper samples to the proper lab to get confirmation,” Rollo said.

Infected animals should be isolated and watched for a secondary infection once the blisters burst.

The infection will reportedly run its course in two to three weeks and animals will begin healing.

VSV rarely results in the animal’s death.

The good news, according to Rollo, is cooler weather will likely mean fewer cases of VSV.

“We are already seeing a reduced number of cases. Our peak was probably the week of July 21, and since then, we are gradually getting fewer and fewer each week,” Rollo said.

The first VSV case was reported in Kinney County June 21.

Since then, infections have been confirmed in seven states: Colorado, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wyoming, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS).