By Julie Tomascik

Editor

The phone rings and Craig Miller answers, expecting the usual—an update on hunting conditions.

But what he heard would change his life forever.

“I got a phone call from a deer hunter on our property. He said he saw two dead cows,” Craig said. “While we were on the phone, he told me two more were going down.”

Craig recalled that September day in 2013 when he rushed to his truck and headed to the ranch in Talpa. What he found wouldn’t be the worst of it.

About nine cows were dead around the stock tank. Naturally, he figured the water was contaminated.

So, he tried to move nearby cows away from the tank. The harder he pushed, the faster they seemed to die. And his trouble didn’t end there.

Cows were dying all throughout the pasture.

It wasn’t the water.

Craig called Mark Swening, the veterinarian in Coleman, who arrived a couple of hours later.

During the post-mortem evaluation, he found the blood was dark brown.

He pulled fluid from the eyeball and the rumen for additional tests.

The next day, Craig and his wife, Treasa, returned to survey the damage and find the rest of their cows.

Instead, they found more dead cows and orphaned calves scattered around. Most of them were in a centralized location—around the power lines that crossed the property.

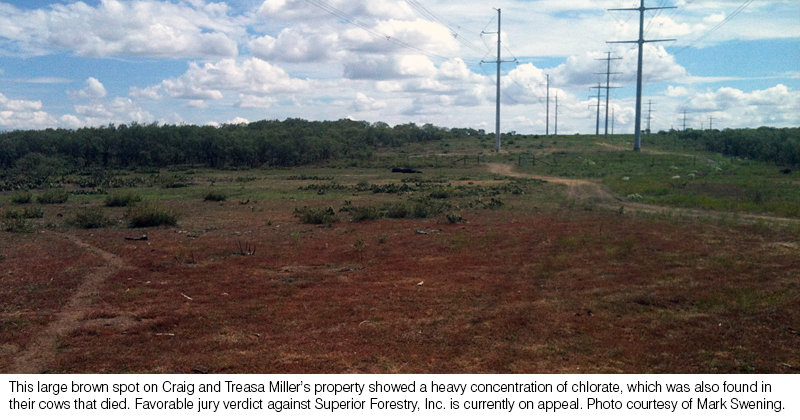

He then noticed a large brown circle near the power lines.

The Millers didn’t know what happened.

Then, the test results came back a few days later, showing a heavy concentration of chlorate in the cow’s system.

But where did it come from?

Trying to make sense of the situation, the veterinarian also took soil samples in the large brown spot, and lab results showed about 20,000 times more than the natural level of chlorate in the soil.

That spot was directly under the power lines.

“There’s no question of where it happened,” Craig said. “It’s what happened, how it happened and who did it that we don’t really know.”

The most recent activity on the property had been by a contracted company, Superior Forestry Service, Inc. The company had been hired by Oncor and Horse Hollow, who have transmission lines running through the Miller’s property, to spray mesquites along the rights of ways.

Superior claims they weren’t on the property in 2013, the year the cows died and the large, brown spot appeared.

The Millers had some suspicions with phone records, GPS positions, company documents and more circumstantial evidence pointing toward Superior being on their property.

The chemical spill, which could have been accidental or intentional, occurred along the easement. Chlorate, the chemical found in the soil and in the cows, had been banned by the Environmental Protection Agency several years earlier for use in rights of ways.

They took their case to court in Ballinger. The jury sided with the Millers. Superior had trespassed on the property and caused the death of their cattle.

Ben Woodward, a district judge in San Angelo, however, overturned the ruling.

Now the Millers are still fighting, seeking justice for the negative impact this has on their livelihood.

At the heart of the situation is eminent domain.

The Millers had their land taken by power companies and have suffered seemingly insurmountable damages in the years following.

“We’re just distraught over this, even though it’s been going on for so long,” Craig said. “It’s not right to be treated this way. It’s not right that eminent domain has brought us to this point.”

Losing the cows has been a financial difficulty. But knowing they’ll have to sell Craig’s inheritance investment is devastating.

“The land was passed down to me from my grandmother’s side, and we sold it to reinvest in this property—one we could make a living from raising cattle,” Craig said. “But now we can’t afford to keep it. We’re basically giving up.”

It’s been a long four years for the couple.

Their case is still in the Third Court of Appeals.

Court hearings, filing appeals and consulting with their lawyer has culminated in hundreds of pages of court documents that will hopefully lead to a positive outcome.

“Things in life aren’t fair. I know that,” he said. “But we’re having to sell what we worked nearly 40 years for and were going to retire on. Now we don’t know what we’ll do. We can only hope.”

The r

What did Ben Woodward state his position on? and how do we put a stop to it? questions I’m sure everyone has

So much proof our judges are paid off it is sick!

I’m praying for the courts to use their head for a change and do what’s RIGHT! With all the oil activity creating rights-of-way across ranch land everywhere in Texas, the Millers won’t be the only ones facing this kind of challenge. For a big company to prevail in this situation is UNAMERICAN! We who work the land deserve to be able to make a living without fear of interference and harm from entities like the ones who caused the Millers to suffer irreparable damage to his cattle. It shouldn’t cost him everything he worked and saved for!

I surely don’t think that is either. Now a days people can get by with anything if they have judges and other people on their side

Ben Woodward is an excellent judge and the absolute opposite of any type of judge who would ever take a payoff or anything like that. The evidence requirements to prove that something occurred circumstantially are very high. You can thank the Texas Supreme Court for that. Unfortunately, District Courts have no choice but to apply Texas law as it is handed down to them. There was apparently no direct evidence that the company sued actually put the chemical on the right of way. The Court then has to parse whether the evidence presented was sufficient. This is a sad result of nearly 30 years of a Supreme Court that has all 9 members from one party and with one mindset, to protect big business. The Texas Farm Bureau has been one of the biggest supporters of the Supreme Court and that mindset. Things like this are the sad result.

Gee, Guy, one would think you were a registered Democrat or something from your comments.

You need to get over this BS about Republicans being for the corporations and Democrats for the “Little Guy.” Democrats have been on the take from Corporate America for generations but have been very good at covering their tracks, which is not too hard when you have an aiding and abetting media.

Private Property Rights is what Texas Farm Bureau is fighting for , this is just another example of overreach once you have a right-a-way through your property. Most, if not all utility companys, us sub-contractors to keep right-a-way clean. Is the utility Co liable. We need better Private Property Rights..

Fair is fair! What are the facts? How do you get the goods on the judge and the power company? Money corrupts.

Prayers with this family!!

There is Government movement to get people into city’s out of rural areas