The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced Tuesday an atypical case of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), a neurologic disease of cattle, in an 11-year-old cow in Alabama.

Officials said at no time did the case present a risk to the food supply or to human health.

USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s (APHIS) National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) determined the cow was positive for atypical (L-type) BSE. The animal was showing clinical signs and was found through routine surveillance at an Alabama livestock market.

“We do a trace-back on the animal. We do epidemiology on animals that this animal is housed with and any offspring. So we’ll go back and look at those, and possibly either monitor them, or purchase them, and the process to check them to see if they have any,” said Dr. Jack Shere, USDA chief veterinarian. “With atypical, you wouldn’t expect this to be. It isn’t a disease that spreads from animal to animal. It’s spontaneous, so our epidemiology should not be that difficult.”

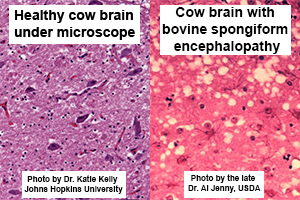

APHIS said BSE is not contagious and exists in two types—classical and atypical. Classical BSE is the form that occurred primarily in the United Kingdom, beginning in the late 1980s, and it has been linked to variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) in people. The primary source of infection for classical BSE is feed contaminated with the infectious prion agent, such as meat-and-bone meal containing protein derived from rendered infected cattle. Regulations from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have prohibited the inclusion of mammalian protein in feed for cattle and other ruminants since 1997 and have also prohibited high risk tissue materials in all animal feed since 2009.

Shere said many levels of BSE prevention and detection have been put in place over the last few years.

“We remove from animals presented at slaughter the specified risk materials or parts of the animal that might contain the BSE protein prion and possibly transmit the disease. All animals that go to slaughter have these materials removed,” Shere said. “The second safeguard that we follow is a strong feed ban, which prevents mammalian protein being fed back to any type of ruminant. And another important component of our system is of course our ongoing surveillance program that allows USDA to detect the disease as it exists at very low levels in cattle populations. We use to sample up to 40,000. We’re currently sampling 25,000 animals per year. We’re well above the standards set by OIE (World Organization for Animal Health) for that type of surveillance.”

Atypical BSE generally occurs in older cattle, usually eight years of age or older. It seems to arise rarely and spontaneously in all cattle populations, according to officials.

The Alabama case is the nation’s fifth detection of BSE. Of the four previous U.S. cases, the first was a case of classical BSE that was imported from Canada. The rest have been atypical (H- or L-type) BSE.

The OIE has recognized the United States as negligible risk for BSE. Atypical BSE cases do not impact official BSE risk status recognition, as this form of the disease is believed to occur spontaneously in all cattle populations at a very low rate. According to APHIS, the finding of an atypical case will not change the negligible risk status of the United States and should not lead to any trade issues.